Synopsis

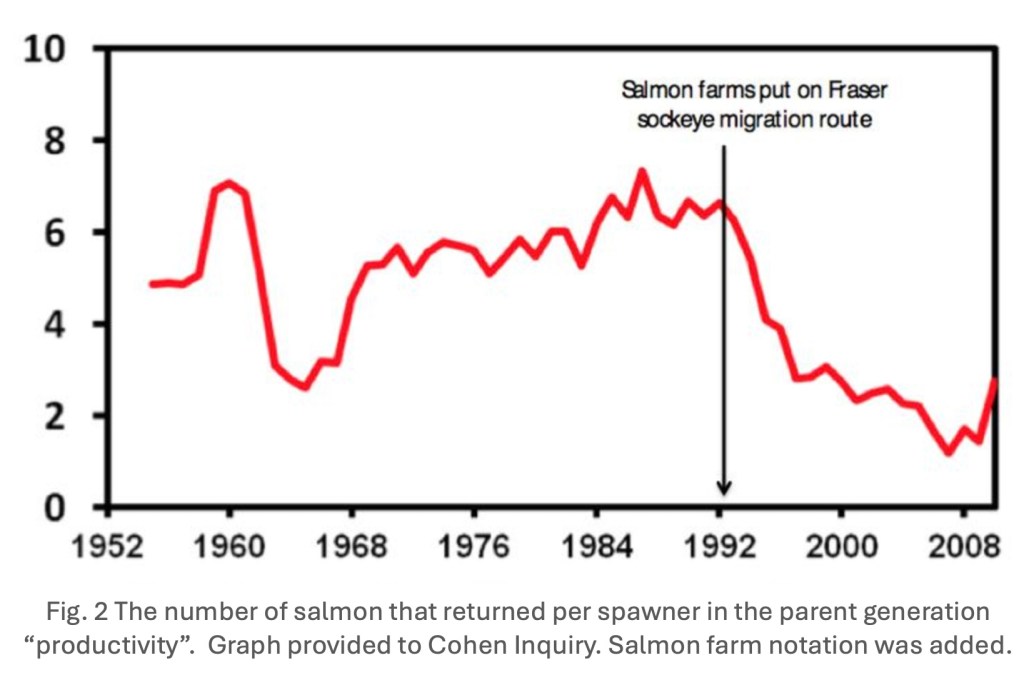

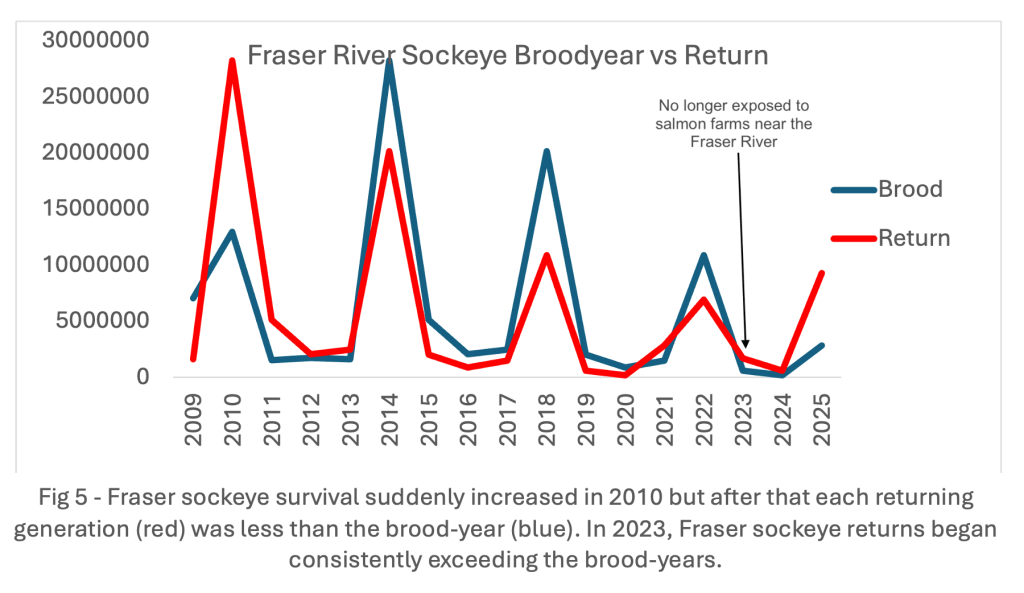

When salmon farms were placed on the Fraser River sockeye migration route in 1992, Fraser sockeye productivity went into decline. When the government of Canada removed those farms in 2021, every generation Fraser sockeye since then has significantly rebounded.

When pink salmon in the Broughton Archipelago crashed in 2002, the Province of BC heavily restricted operation of the local salmon farms. Broughton pink salmon egg to adult survival rate surged to the highest rate ever recorded for the species. When the BC government withdrew their restrictions, Broughton pinks declined, and the commercial salmon fishery was permanently closed. When First Nations began removing salmon farms from the Broughton in 2018, pink salmon returns doubled and then doubled again the next generation. Since then, Broughton pink salmon have continued to rebound, except for the one river still exposed to salmon farms, the Glendale River, which has declined to1.5% of average returns.

In 2024, we saw the return of the first generation of 4-year-old chum salmon that went to sea after most salmon farms between Vancouver Island and the mainland had been removed. DFO forecasted a poor return. Chum returns were poor on the Central Coast and other regions where salmon farms operate, but from Alert Bay through Washington State 2024 chum salmon returns sky-rocketed up to 22xs above recent generations (Viner River) and a fishery was opened.

Some scientists have travelled to First Nation communities to say they are “uncertain” whether farm salmon pathogens harm wild salmon populations. Other scientists provide evidence of significant harm. This report is the evidence provided by salmon themselves, across years, regions, and species. These data were scattered, hard to see. Approximately 50% of BC salmon farms have been closed and a repeating pattern is emerging. Wild salmon are talking. This is their story.

Salmon Farms 1992-2025

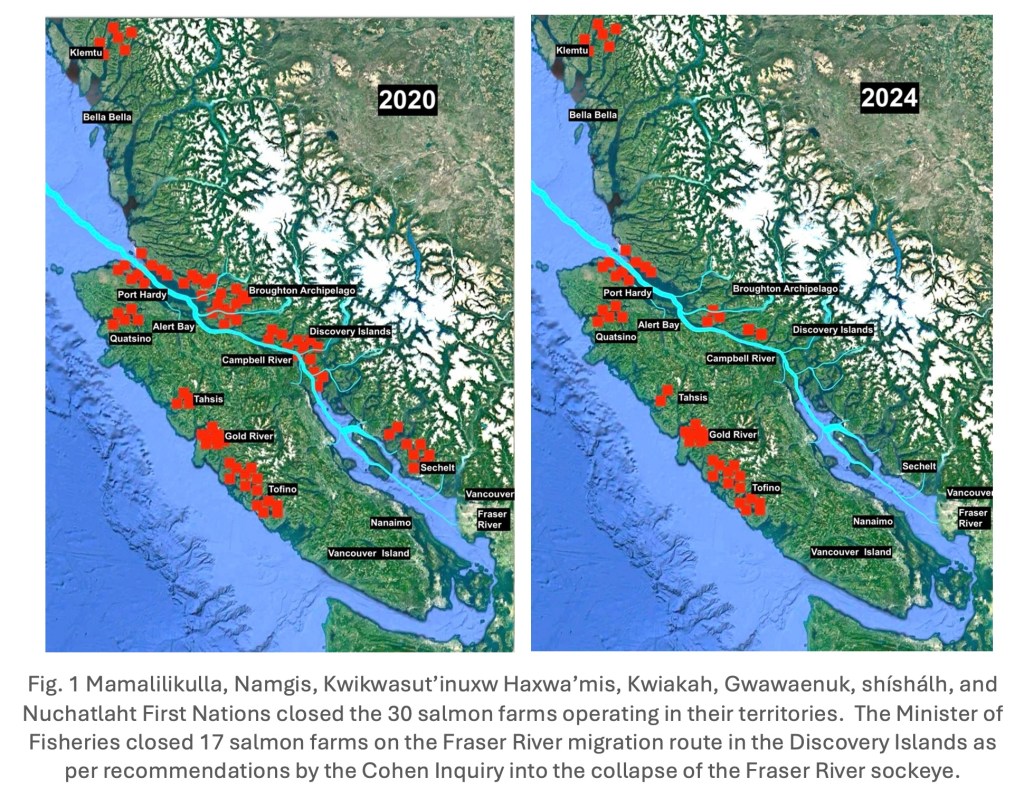

Salmon farms began using the BC coast in the mid-1980s. By the 1990s approximately 115 salmon farms were in operation (Fig 1, left). Beginning in 2018, growing evidence of disease transmission from farm salmon to wild salmon led to the closure of nearly 50% of BC salmon farms to protect wild salmon (Fig 1, right). Did this increase salmon survival?

Fraser River sockeye

December 2020, following recommendation #19 of the $28 million Cohen inquiry[1] into the collapse of the Fraser River sockeye (Fig 2), Minister of Fisheries Bernadette Jordan refused to renew the 17 salmon farm licenses in Discovery Islands. She did this to protect young Fraser sockeye migrating through this region from sea lice and disease proliferating in the feedlot environment inside the farms. The industry was allowed to finish growing the fish already in the pens but not to restock. Most of the farms became empty before the next generation of sockeye went to sea. All salmon farms in the Discovery Islands were closed by June 2021.

Sockeye salmon are largely considered a 4-year fish.

- Year zero – the parents spawn

- Year one – the young sockeye hatch and remain in freshwater

- Year two – the young sockeye go to sea

- Year three – they remain at sea

- Year four – they return as adults and spawn

1992 – 2009

The graph below (Fig 2) submitted to the Cohen Inquiry into the decline of the Fraser River sockeye, shows that the number of spawners (parents) vs the number of offspring had declined steadily since 1992. DFO testimony at the Inquiry stated that by reducing commercial fishing the target number of spawners had reached the spawning grounds annually, but despite this, fewer and fewer sockeye were surviving every generation.

Researchers tracking young sockeye migrating down the Fraser into the ocean report high losses occurred immediately after the fish had passed through the Discovery Islands.

Thus, the Cohen Inquiry recommended closing salmon farms in the Discovery Islands.

2023 – 2025

2022 was the last generation of Fraser sockeye that migrated through salmon farms in the Discovery Islands when they were juveniles on their way to sea and their numbers declined. Every generation since then, that did not migrate as juveniles through those farms, has returned in numbers significantly larger than their brood-year (Fig 3).

2010

While Fraser River sockeye productivity started collapsing in 1992, it unexpectedly increased for one year in 2010, when a brood-year of 13 million produced a return of 28 million. Internal government records provide interesting insight.

During the collapse, an increasing number of Fraser sockeye were mysteriously dying in the river just before spawning. At first this was attributed to high water temperature, but this theory was dismissed in 2006[1],[2]when more sockeye died in cooler water. That year, DFO scientist Dr. Kristi Miller began linking the mass die-offs to a leukemia virus that DFO had discovered in Chinook salmon farms in the Discovery Islands in the early 1990s and had reported in the journal CANCER RESEARCH that it would spread to sockeye. Miller’s finding threatened the salmon farming industry. Her request to test the farm salmon was denied, her research was terminated. Marine Harvest (MOWI) removed all Chinook salmon from their farms by 2008 (Fig 4). The Fraser sockeye that returned in 2010, went to sea in 2008 and thus were the first generation not exposed to Chinook salmon farms since 1992. Then the farms were restocked with Atlantic salmon. The report on the evidence linking Fraser sockeye mortality and Salmon Leukemia is a Cohen Inquiry exhibit.

The 2010 increase in Fraser sockeye productivity lasted only one year. Figure 5 shows the decline of the 2010 broodline when they returned in 2014, 2018, and 2022. They will return in 2026. Meanwhile, beginning in 2023 the 1st generations of sockeye no longer exposed to any salmon farms at the start of their lives at sea as they pass through the Discovery Islands immediately began returning in numbers higher than their parents.

Figure 6 shows daily numbers of four generations of one broodline of sockeye entering the Fraser River. If the extraordinary upward arc of the 1st generation of this broodline not exposed to salmon farms in the Discovery Islands (black line, 2025) is not linked to removal of salmon farms, what did cause it and how can it be maintained?

Broughton Pink Salmon – 2000-2002

In 2000, over two million pink salmon were caught in commercial fisheries in the Broughton Archipelago. Another ~3 million spawned in the Kakweiken, Glendale, and Hada rivers. The following spring (2001) 75% of their offspring were infected with sea lice at levels considered lethal. In 2002, 98% of this generation failed to return (Fig 7).

An investigation into the collapse concluded “Sea Lice are a serious problem for both industry [salmon farms] and wild salmon”. In response the Province of BC launched their Pink Salmon Action Plan in 2003 requiring all salmon farms on the primary Broughton pink salmon migration route either be empty or stocked only with young Atlantic salmon direct from a hatchery and so not yet infested with sea lice.

The response was significant. In 2004, pink salmon survival, typically 0.8 – 5.4%, jumped to 34.2%, “the highest marine survival of pink salmon recorded”. Broughton pink salmon appeared to be on the road to recovery, but the Province of BC dropped the 2003 restrictions on salmon farm activity, pink salmon runs declined again and commercial salmon fishing in the Broughton Archipelago was terminated.

Broughton Pink Salmon – 2018

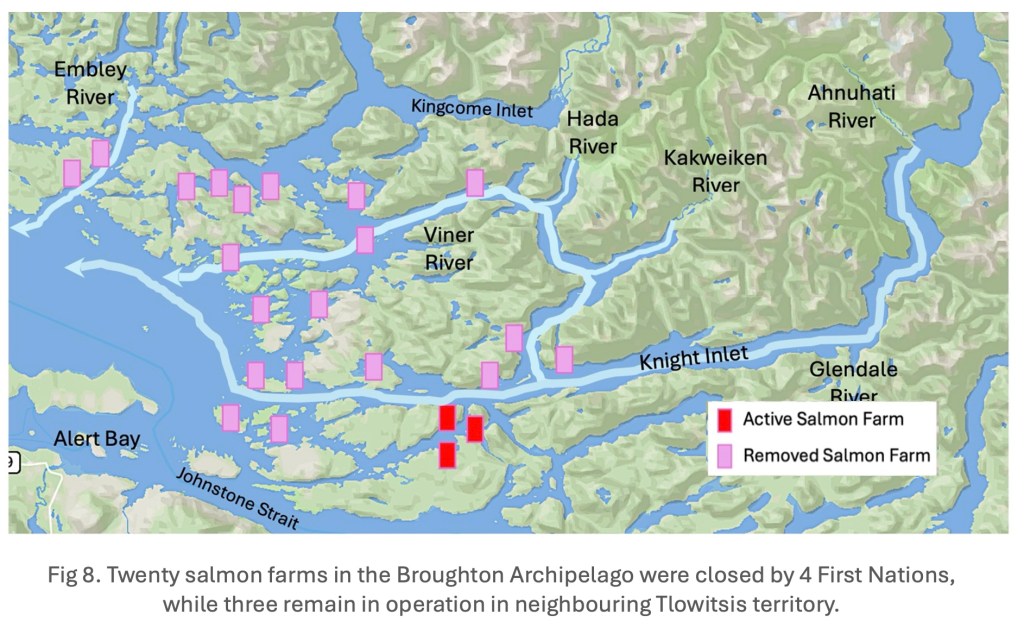

In 2018, Mamalilikulla, Namgis, Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis and Gwawaenuk began the closure of 20 salmon farms in the Broughton Archipelago to restore their wild salmon.

In 2022, the first return of Hada River pink salmon after nearby salmon farms had been closed increased 10-fold (~1000 to 10,000 fish), and doubled again in 2024 to 20,000. Ahnuhati pinks salmon, hovering at 11,879 for the past three generations, rebounded to 106,453. Embley pink salmon shot up ten-fold from an average of 283 fish over the previous three generations to 2,241. Because Tlowitsis allow 3 salmon farms to continue operating (Fig 8), an unintended experiment testing the impact of salmon farm is providing critical information.

The experiment – results

Hada, Kakweiken, Ahnuhati and Glendale are a cluster of rivers sited on the mainland in the eastern portion of the Broughton Archipelago (Fig 8). Twenty-five years of tracking Broughton juvenile salmon informs us that most young pink salmon from the Hada, Kakweiken and Ahnuhati rivers migrate to sea via Tribune Channel, while at least some portion of juvenile Glendale pinks migrate to sea along the southern shore of Knight Inlet and thus are directly exposed to farm salmon effluent flowing from three Atlantic salmon farms into Knight Inlet (Fig 9).

Unfortunately, there were no salmon counts reported for Kakweiken in 2025, but pink salmon returns to Hada and Ahnuhati increased significantly, again, while Glendale River pinks declined (Fig 9). The 2025 Glendale pink salmon return not only fell below their brood-year, but they also crashed to 1.5% of their odd-year cycle average from 169,976 to 2,582 fish. Something catastrophic specifically impacted only the Glendale, a river with spawning channels where international guests flock to view grizzly bears.

When reviewing the potential impact of salmon farms, it is important to account for the farm salmon cycle. Salmon farming companies often synchronize harvest all their farms in each area to ensure that when they bring young Atlantic salmon from their hatcheries, the young salmon are not infected by nearby older generations. Thus, the maximum risk from salmon farms in Clio Channel, for example, may occur every other year and not annually. The three companies operating in BC, occupy separate regions, not willing risk cross-contamination between companies. Salmon migrating past several companies may face alternating risks as they pass through waters used to flush farms belonging to different companies.

Chum salmon

The first generation of chum salmon that went to sea after most salmon farms had been closed between eastern Vancouver Island and the mainland returned in 2024.

DFO forecasted a poor 2024 chum salmon return to the BC coast. Instead, chum salmon sky-rocketed in a pattern matching the regions where salmon farms had been removed (Fig 10). Note the large increases in the Broughton and Discovery Islands/Strait of Georgia (green circles). Viner chum increased 12xs over recent averages. Theodosia increased from an average of 4,500 to 52,000. Meanwhile Central Coast, Quatsino, Nootka – where salmon farms continue to operate -chum returns remained depressed. Full Report

Clayoquot provides intriguing evidence. The number of lice permitted per farm salmon was halved in 2021 when this generation of chum salmon went to sea. Is this why they survived at a higher rate than Quatsino and Nootka? This information contributes to the understanding of the impact of the unnaturally high larval sea lice populations released by infected salmon farms. DFO reports the fish farming company operating in Clayoquot Sound (Cermaq) struggled to maintain the low lice levels in subsequent years and ceased all public sea lice reporting in 2024. It is unclear if Cermaq was able to maintain the lower lice restriction. Detailed report. To date the global salmon farming industry continues to report failure to control sea lice (Newfoundland, Norway, Scotland).

Summary

The relationship between dramatic increases in wild salmon returns after removal of farm salmon has repeated for 20 years. British Columbia is the first place in the world to remove salmon farms and so everything we are learning here is new.

Removing farm salmon pathogens cannot protect wild salmon from other impacts such as forest fires, low water, warm water or high seas fisheries. For example, the millions of chum salmon eggs destroyed by intense flooding in 2021 will reduce chum salmon returns in 2025. But this raises the question – given that the changing climate is making survival more difficult for salmon, what do we do with evidence in this report?

Canada has recognized this threat to wild salmon, declaring a ban on netpen salmon farming by mid 2029. Over 120 First Nations agree. Industry and other First Nations are working to remove this ban and expand the industry. It unclear whether the Carney government will follow through with the ban.

When the Province of BC lifted its 2003 restrictions on Broughton salmon farms, wild salmon slipped back into decline. When First Nations removed those farms, Broughton salmon increased again. When salmon farms arrived in the Discovery Islands Fraser sockeye declined, when they were removed Fraser sockeye and chum rebounded. What will happen if the farms are allowed to return? If salmon farms were removed from the Central Coast, Quatsino, Port Hardy, Nootka and Clayoquot would the same rebound seen elsewhere occur? What will happen if the belt of salmon farms across off Port Hardy Island (Fig 1) are infected with virulent disease as Fraser, mainland inlet and east Vancouver Island salmon are exposed?

Wild salmon have accomplished miraculous returns in all regions where salmon farms have been removed.

For further information:

Broughton First Nation Science

Salmon Coast Field Station Research in Broughton

Impact of Removing Salmon Farms

Movie – Salmon Confidential

[1] Cohen Commission Report Volume 3

[1] https://www3.carleton.ca/fecpl/pdfs/Sockeye_Fisheries_MS.pdf

[2] https://alexandramortonblog.com/wp-content/uploads/morton-report–what-is-happening-to-fraser-sockeye-aug-16-00372318-copy.pdf

Comments

2 responses to “How salmon respond to closure of salmon farms”

This is fantastic news!

Thank you Alexandra Morton for not burning out.

You are a true Canadian Hero!

Gaia thanks you too!

Governments owe you an apology, and the rest of us owe you a debt of gratitude!

There needs to be a commitment to close all remaining open net fish farms by the timeframe prescribed by the federal government. For years DFO has been negligent in managing the closing of open net pens. They have ignored the science that was staring them in the face. Close the open net pens and require MOWI and others to proceed to land based operations